Did you hear the one about the Russian Jew from Minnesota who walked into a Chicago bar to sell the owner Swedish booze?

Only in America!

Did you hear the one about the Russian Jew from Minnesota who walked into a Chicago bar to sell the owner Swedish booze? Sure, it sounds like the set-up of a bad joke, but it's a true story and one entertainingly told by journalist Josh Noel in Malört: The Redemption of a Revered and Reviled Spirit.

George Brode was born in Duluth, Minnesota, in 1909, the fourth of five children. His parents had fled Tsar Nicholas's crumbling empire and stayed briefly in England and Canada.

The Brodes (then Broides) moved to bustling Chicago when George was three years old. He grew up in a cacophonous immigrant neighborhood in Humboldt Park—a two hours' walk and a world away from the city's downtown Loop. But George had dreams and the pep to chase them.

He did well in public school and tested and bettered himself through debate club and sports, all while holding a job. George went to Crane Junior College for a few semesters, then moved up to Northwestern University to finish his studies with a law degree.

There he also met Fritzi Bielzoff, whom he married. It was a lucky break. She was good to George and bore him three sons. Her dad ran a liquor company and hired George to help him sell hooch. The money flowed in. Prohibition had just ended, and there was pent-up demand for strong drink.

In 1934, as George told it, a Swedish guy named Carl Jeppson offered to sell his brand of homemade booze. George took him up on that offer, and Malört was added to the portfolio of Bielzoff Products.

By 1945, George and his young family were living in a new apartment near Lake Michigan, and he was rich enough to buy his father-in-law's company. He was briefly atop the world, then crashed hard. The U.S. government sent George to prison for draft dodging. George served a year, but his troubles continued after he exited the penitentiary in Terra Haute. The liquor business went south, and he was forced to sell the liquor company and all its brands to a competitor.

Except for Jeppson's Malört.

Why he held onto the brand is unclear. Its charms were few. Malört is made by steeping cuts of wormwood (Artemisia absinthium, a famously bitter herb) in neutral grain spirits, a.k.a. raw ethyl alcohol. Noel notes that wormwood "earns a grim cameo" in the Book of Revelation, which depicts much of humanity dead after a star named wormwood fell to earth and tainted the water.

Certainly the public had little appetite for it. Malört has an unsettling yellowish color, and the taste, well, it's not good. There are plenty of bitter boozes out there, like Fernet Branca and Aperol. But Jeppson's is in another league.

"It tastes like a hobo's Band-Aid," one drinker pithily noted. Another characterized a shot of Malört as initially tasting of grapefruit and honey that then delivers an aftertaste of gasoline, earwax, and bug spray. A character in the 2013 film Drinking Buddies likened it to "swallowing a burnt condom full of gas." Others who have gulped a shot of it have still harsher words unfit for recounting in a classy publication.

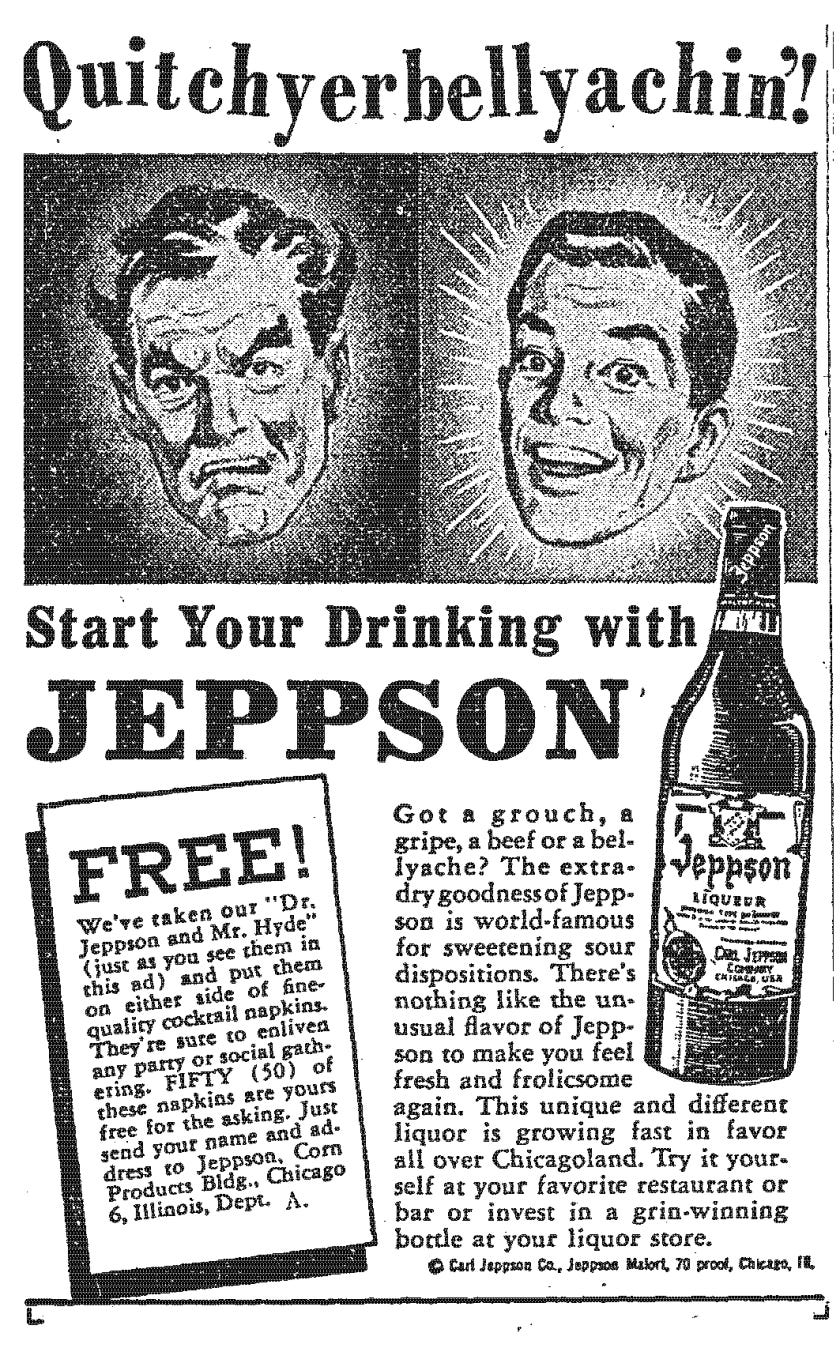

George clung to the brand and paid his bills by working as a probate attorney. He pleaded with bars and shops to stock it and ginned up zany advertisements that embraced its awfulness. Initially, he tried a soft sell that pitched Malört as an acquired taste, like olives and oysters.

Then he embraced confrontational bravado. "Are you man enough to drink our two-fisted liquor?" asked a little booklet hung from a string on the bottle's neck. "It's a real man's drink," insisted another. His campaign could not be accused of understatement, seeing as other Jeppson advertisements told men who wore berets or liked the color baby blue that they were not capable of handling a belt of Malört.

None of which made up for a truth that George admitted aloud: "Most first-time drinkers of Jeppson Malört are repelled by our liquor." Sales peaked at 3,846 12-bottle cases in 1973, then crumbled. The company hit its nadir in 1988. Not a drop of Malört was distilled. A decade later, George died.

Astonishingly, Malört lived on, and then thrived. George left the company to Pat Gabelick, his long-serving secretary and companion. (Fritzi had died in 1977.) Pat kept the company above water, barely.

About 15 years ago, Pat unexpectedly got a boost from a few young guys who had serendipitously discovered Malört. One fellow started posting photos of people trying a shot of Jeppson's for the first time. His Flickr "Malört Face" page went viral and goaded more people to try it.

Another guy became fascinated by Malört's Swedish roots and local history. He volunteered to serve as the company's archivist and to educate Chicagoans about it. Pat agreed with some bafflement.

Then there was the imp who said Malört reminded him of "baby aspirin wrapped in a grapefruit peel, bound with rubber bands and then soaked in well gin." Nonetheless, he loved it and sold Malört T-shirts and eventually persuaded Pat to make him marketing director.

Word spread and sales began to rise. This younger generation thought Malört's history and dreadful taste were selling points. They would buy shots of the bitter booze to friends visiting from out of town. Or they ordered a round when there was an occasion to celebrate, like a new job. One bar held a Malört night where guests try it and write down their visceral reactions, which became quips retold:

"Malört: Remind yourself why you quit drinking."

"Drink Malört, it's easier than telling people you have nothing to live for."

"Tonight's the night you fight your dad."

Another Chicago guy started a Malört race. Though it is only five kilometers long, the race is brutal: Competitors had to do a shot, run the 3.2 miles to the finish line, where they gulp another shot, and drink a beer.

The hooch became so popular that a big liquor company tried to gobble it up and a couple of Chicago microdistilleries began peddling their own versions of Malört.

Pat sold the company a few years ago to another drinks company and retired. The craze has not ended. Noel reports the most recent annual figures show 30,000 cases were sold, the most ever.

So, yes, Malört is both a joke and a true tale. But it also is something much more—it's a great American story.